The story of the near west side, before IUPUI came to be.

by Paris Garnier

When Paula Brooks was 18 years old, she left her home in Ransom Place to attend college on the east coast. She returned home to care for her ailing mother eight years ago. Now 56, she discovered just how much her neighborhood, which her family had lived in since the ‘30s, had changed in her absence.

“I’m old enough to remember when it was a neighborhood from basically from White River all the way over to Capitol Street,” she said.

But the radical shift Brooks experienced is not the first time the near-west side of Indianapolis has changed. Many students wonder what came before IUPUI and are often surprised to learn that an almost century old, predominately black neighborhood occupied the area.

The near-west side of Indianapolis was rather empty until the mid-1800s when African Americans moved into the area. European immigrant families settled as well, but it was still primarily a black community. The IU medical center would come shortly after in the Civil War.

According to professor Paul Mullins, an anthropology teacher at IUPUI with a focus in race and material culture, residents built “modest, vernacular wooden homes” on small lots that went up to the street. New additions were built as necessary. A lack of running sewage and trash collection that continued into the 1950s meant backyards were occupied by privies or trash pits. Many tenants were renters.

Although the houses were hodgepodge, the community was strong. Churches, schools, and the Madame C.J. Walker Theatre allowed the neighborhood to develop and attract more African American residents from the South seeking work during the depression and second World War.

“There’s a community to come to, and at least a different sort of racist violence than many people of color had experienced in the South,” Mullins explained.

The houses themselves, however, began to decline as early as the ‘30s. But they remained unchanged and undisturbed by outsiders until the ‘50s, when urban reconstruction swept the nation. Using federal funds, Indianapolis followed the trend of “slum clearance” and started pushing residents out.

“[Slum clearance] almost always was code for moving out inner city predominantly black neighborhoods like this one,” Mullins said. “This happens in Chicago, this happens in Detroit, Cleveland, New York, Philadelphia, D.C., in somewhat different sorts of ways, but it's all cut from the same fabric.”

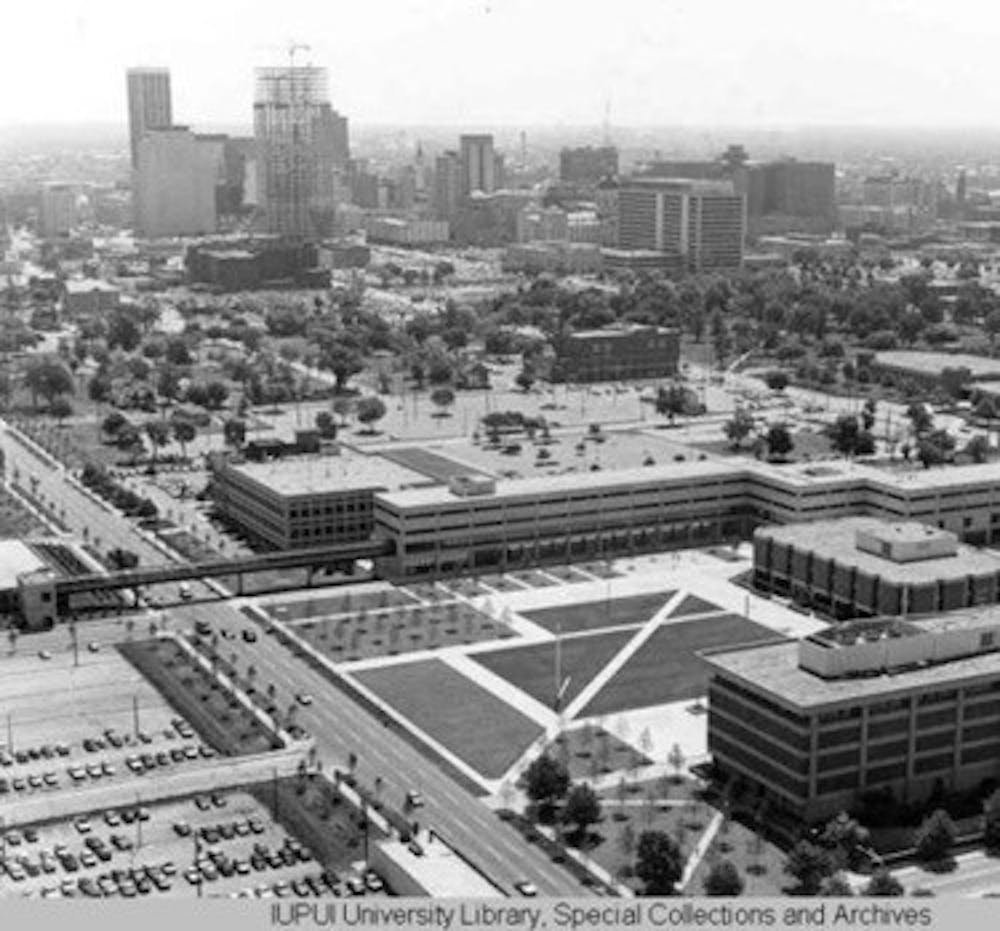

At the same time, Indiana University and Purdue University were developing plans for a downtown satellite campus. Cavanaugh, Taylor, and the lecture hall were built first. Land for parking and future projects was at a premium. There was a dissonance between residents and those attending school.

Then in 1962, city officials stopped taking federal clearance money, which prompted IUPUI to hire private contractors to purchase each individual house in the area. Landlords sold the property and the university paid fairly, but it was never enough to buy a better house elsewhere.

And one by one, residents left of their own volition. When someone decided to move, IUPUI lent a van and then demolished the property immediately afterward. The lot was often paved right up to the neighbor’s fencing, which would motivate them to leave. Many went into Haughville.

This trend continued into the ‘80s, when the last residents moved out. Some wonder how this particular neighborhood, with space available elsewhere, could have been displaced. The answer is simple: racism.

“It’s not a coincidence,” Mullins said. “The discussion was always focused on the west side and when the highway construction was being planned, lots of that discussion centered on predominately black communities, too.”

The legacy of the neighborhood can be found in Ransom Place today.

“If you wanted to see what this neighborhood looked like in the 1950s--at least in terms of architectural style, density of settlement, size of houses--Ransom Place is kind of the last surviving remnants,” Mullins said. “Those handful of blocks are basically all that survives of this neighborhood.”

But IUPUI continues to impact life in Ransom Place. Expanding student housing leads to apartments encroaching on historical property that cannot handle such additions. The remaining houses sit close to narrow streets with high-speed traffic.

“It’s changed drastically, and it’s even changed in the eight years since I’ve been back just with the university deciding that it wanted to become more of a campus-like university rather than a commuter school,” Brooks said. “You’re bringing in 200 more people but you’re not improving the infrastructure, so we have a serious issue with parking.”

Brooks has expressed a sense of reassurance in IUPUI’s Social Justice program and believes Ransom Place will not go unnoticed. Mullins said that while he champions IUPUI and his experiences here, the physical history of the land has to be addressed in a constructive way.

“We have hundreds of acres here that we acquired from people of color and leveraged through the power of the state,” he said. “We can’t ignore that.”

Denizens Displaced

Heads up! This article was imported from a previous version of The Campus Citizen. If you notice any issues, please let us know.

A house in the neighborhood in the 1950s. (Image from IUPUI's digital collection.)

The neighborhood in 1940. (Image from IUPUI's digital collection.)

IUPUI in 1981. (Image form IUPUI's digital collections.)