As tourists wander the streets of modern Rome, imaginations go rampant trying to recreate the rubble that remains from one of the world’s largest empires. The republican Forum Romanum, once adorned with lavish basilicae, massive temples, and decorative monuments, is all but column bases, temple fragments, and acid-washed monuments. However, Dr. Elizabeth Thill, a classics professor at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, is working with a team to recreate what was once the largest city in the western world.

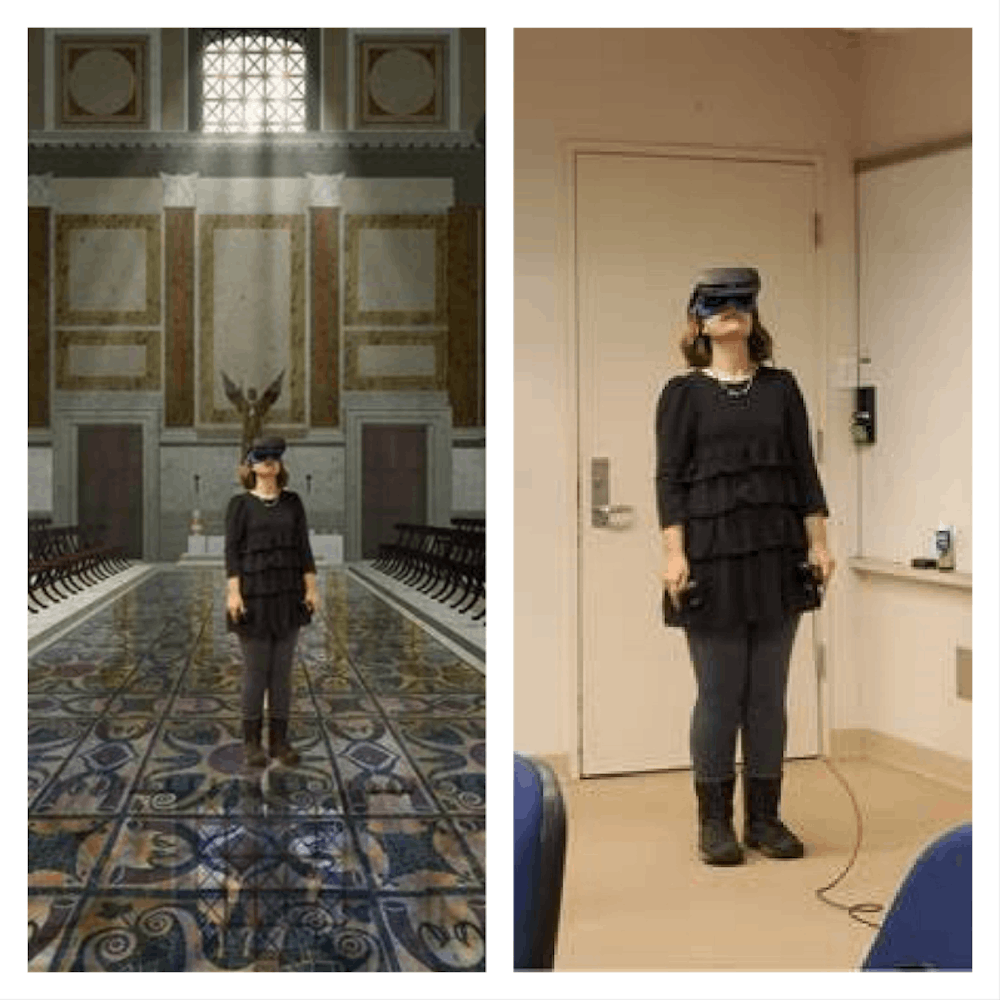

The application of virtual reality has created new possibilities for scholars and students alike to dive into history books. VR provides an opportunity to interact with history in a way that once was thought possible only by time travel. Fortunately for Thill, an Oculus device can now serve as a virtual playground of endless opportunity, eliminating any need for a magical time machine.

“VR is definitely going to change the way we learn,” Thill said. “If I can show my students the actual buildings in Google Earth, there’s really no justification to make everyone go back to staring at 2D pictures, angle by angle.”

Thill developed her love for archeology through reading books and watching programs on TV, notably on The Learning Channel, now TLC, and the History Channel. Her interest in classics grew during high school due to a three-year Latin requirement. With a strong interest already brewing for archaeology, a family trip to Ireland sealed her passion.

“We visited a lot of archaeological sites,” Thill said. “I was hooked after that. I liked archaeology’s mixture of storytelling and quantitative data.”

Following high school, Thill obtained her bachelor’s and master’s in classical archaeology from the University of Michigan. Five years later, she earned a doctorate from the University of North Carolina. During her time in college and thereafter, Thill gained valuable experience within her field by taking visits abroad to Italy and Cyprus to excavate, study, and perform research.

“I love working abroad,” she said. “It’s always a challenge and you learn so much, about archaeology, about other cultures, about yourself. It requires a lot of flexibility and faith that things will turn out ok in the end, and it always has for me.”

Thill always knew she could follow similar footsteps as her father, who was also a professor. In 2013, Thill landed a job as an Assistant Professor of Classical Studies at IUPUI. One year later she became the Program Director of Classical Studies, a title which she continues to retain.

“I think it is critical that people learn about the past, as well as how we learn about the past, so they can think critically for themselves about how the past informs their current lives.”

The first use of virtual reality can date back to 1957 when American cinematographer Morton Heilig invented the Sensorama. According to G2, the machine stimulated a user’s sense of sight, sound, touch, and smell through a screen, speakers, oscillating fans, and contraptions that emitted smells. Fast forward to 2010 and Palmer Luckey developed what would end up becoming the Oculus Rift.

Ryan Knapp, head of the University Library’s Virtual Reality Lab, had the opportunity to experience VR in its early days.

“My first experience with VR was at an arcade in 1996,” he said. “Back then the tech was very primitive and nausea inducing, but you could see its potential.”

As for Thill, she hadn’t experienced virtual reality until the summer of 2019. Once introduced, there was no going back.

“I had never done VR before Summer 2019, when Ryan Knapp came on to the Great Marble Map of Rome Project (GMMRP) and suggested we put some of the fragment scans in VR. This had always been on my wish list, but frankly I didn’t think it would be possible for years to come. Once they showed me Google Earth, I knew I couldn’t go back to teaching the way that I had.”

The GMMRP is a project that originated through Thill’s co-directors, Dr. Richard Talbert of UNC-Chapel Hill and Dr. Francesca de Caprariis of the Musei Capitolini, who were setting forth new projects on the Marble Map of Rome, an ancient map of Rome that was located in the Temple of Peace, also known as the Forum of Vespasian. Thill brought everyone together and decided to add her own contribution by adding new virtual scans of the map.

Likewise, prior to meeting Thill, Knapp had little experience within classical art and architecture.

“I honestly didn’t anticipate there being a possible case for it [classics] with VR,” Knapp said. “Fast-forward 6 months and I can say that working with Dr. Thill to virtually reconstruct Rome for classroom use has been the highlight of my 19-year career.”

Thill’s overall goal in using virtual reality within education and research is to increase public engagement and advance research within the ancient world.

“In terms of public engagement, VR allows people to experience ancient buildings and sculptures much closer to an experience in person,” she said. “In terms of research, VR allows you to test hypotheses in new ways, not only in terms of ease (moving sculptures of fragments with a wave of your hand) but also experience (seeing objects or elements at their original height).”

According to student Joshua Mefford, Thill’s use of VR in the classroom has been a success.

“My impression of the VR experience in this class [Roman Archaeology] is that it seems to be very beneficial,” he said. “I especially like how it can provide experiences that one might only receive otherwise through an expensive study abroad program.”

The application of virtual reality within education is still fresh. With VR expenses declining, Universities across the world are picking up the technology with a primary focus on science, medicine, and engineering. However, VR has potential beyond those practices.

“VR allows us to simulate a wide range of situations and control all of the variables within an environment,” Knapp said. “This can be useful for demonstrating specific ideas and concepts, and for placing users into a precisely controlled situation.”

A particular example of this potential is not only shown through Thill’s class, but through other IUPUI classes adopting the technology as well.

“This year we’ve licensed software called “Embodied Labs” for a Health and Human Sciences course which allows a student to experience a first person perspective of what it’s like to suffer from a variety of medical conditions including Alzheimer’s, Dementia, Parkinson’s and others,” Knapp said.

However, due to the technology still being novel, users can experience some downsides. Thill understands, like any reconstruction, VR can make things seem final, when in reality they’re debated.

Mefford sees similar issues with the technology.

“The main issue with VR in the classroom is likely that, as one could see in our own class, it can have times where it is either inaccurate, or buggy.”

Regardless of the critiques, virtual reality only continues to expand with time. It might not be long before the technology finds its way into every classroom. Whether it’s a history class, or medically related, VR has practical uses that sometimes cannot be obtained elsewhere.

“It won’t happen overnight, but almost certainly and inevitably will become part of the classroom repertoire of educational tech,” Knapp said. “VR holds the potential to bring about possibilities that were once hard to imagine or thought to be impossible.”

Glancing at History Through a Virtual Lens

Heads up! This article was imported from a previous version of The Campus Citizen. If you notice any issues, please let us know.