Artificial intelligence is rapidly reshaping higher education, altering how students complete assignments and how professors safeguard academic integrity. At Indiana University Indianapolis, the debate reflects a broader national divide: Some see AI as an essential tool for the future workforce, while others warn it undermines the very foundation of a college degree.

That paragraph looks like a standard news lede. It wasn’t. It was generated by ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence program created by OpenAI—the same technology which is prompting questions in classrooms about efficiency, ethics and academic honesty.

AI has been around long before it changed how high school and college campuses across the world function. Between the ‘50s and ‘60s, the term “artificial intelligence” was first coined. It was a new era of theories, where researchers wanted to explore technology as a variation of human-like reasoning. The Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS) of the ‘70s manufactured tutoring guidance to students, similar in concept to the ChatGPT known today, though far in development. AI was then seen integrated into the classroom in revolutionary ways.

The difference: Technology then was inaccessible. Students and researchers were often found in the library or nose-deep into an encyclopedia. Technology was a tool used sparingly, and the primary source of human-like thinking came from the humans themselves.

The early systems of AI were underdeveloped. They were strict and stagnant. This input equates to that output. In recent years, AI has evolved to adapt to the information it receives. It can adjust responses by pulling information from across the internet. This machine learning is rooted in probability, making AI smart enough to determine what the best response is.

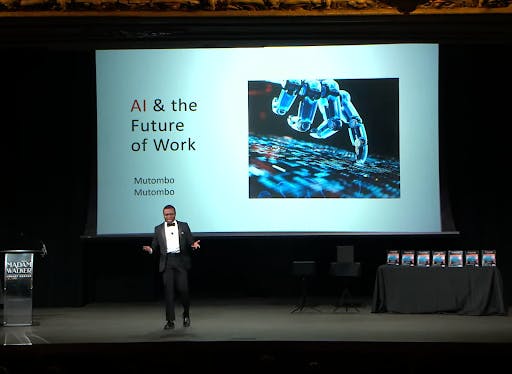

Mutombo (Mike) Mutombo is a data science major at IUI. During the School of Liberal Arts’ Communication Studies department’s 107th Speech Night competition in fall 2024, he presented on the value of embracing AI. For him, part of using AI responsibly means understanding how it works.

“When you truly understand what a tool is, that’s when you know how to make the most of it. For example, some people think when you ask AI a question and it answers like a person, there might be someone behind it,” said Mutombo. “But if you look behind the scenes, it’s mainly working on probabilities—just deciding what word comes next after this word, then the next one after that.”

When ChatGPT became universally available in Nov. 2022, efficiency was redefined. Businesses shifted to using AI for mundane tasks, and government institutions began implementing these technologies.

With rapid adoption came equally rapid anxiety—from online security and privacy to academic plagiarism and even the rise of deepfakes.

For teachers and professors, the main concern was laziness. Students began generating essays with a quick prompt and a few seconds of patience. Struggling on an assignment? The answer was no longer tutoring or office hours—it was ChatGPT.

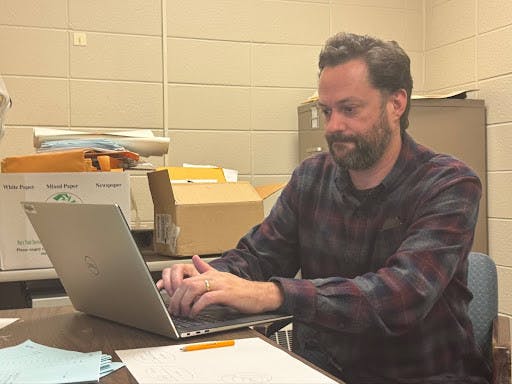

Professor Chad Carmichael, a philosopher and professor at IU Indianapolis, shares these concerns. As an Ivy League alum, doctor in philosophy and published author in over ten academic articles and five book reviews, AI seems like an easy-way-out of critical thinking.

“If students outsource their reading and thinking to ChatGPT, they will get nothing from my course. Nothing,” said Carmichael.

Teachers and professors across the country began noticing patterns since the availability of ChatGPT, some without being told to look for signs of cheating.

“It wasn’t that somebody told me—it’s that I started to see it in the essays,” Carmichael said. “Unlike copy-paste plagiarism, this was very hard to catch.”

Professors like Carmichael began struggling with catching those who were violating academic honesty. He did not want to ask nor accuse students of getting the extra help, but had deep suspicions.

“I could kind of tell, but not with enough confidence that I felt I could even really ask the student. In the past, I’ve not wanted to bring it up unless I was pretty confident,” said Carmichael.

But by summer of 2024, he was catching students misusing AI outright as detection software evolved.

Originality reports were being produced upon student submissions, going through softwares like Turnitin, GPTZero or Copyleaks. These resources do not match the advancement of generative AI, and catching blended writing – both generated content combined with student writing—is a nearly impossible task. Even OpenAI, ChatGPT’s creator, quietly retracted its AI detection software, AI Classifier, due to its poor accuracy in 2023.

There are new tools like Rumi AI which tracks keystrokes and timestamps. Instead of scanning a completed product for AI usage, it focuses on the process itself to flag any unusual activity.

While some professors believe the shift in exploring AI turned into a reliance on it, students tend to embrace it as a form of innovation and an exciting era of human evolution, reflecting a broader generational divide between students who grew up with technology as a lifeline, and professors who remember life before the internet.

“We should embrace AI because there’s really no other option—it’s becoming part of every technology and field of work,” said Mutombo.

Mutombo’s outlook on the matter is influenced by his background. Growing up in the Democratic Republic of Congo and later becoming a refugee in Zimbabwe, access to education was inconsistent, and resources were scarce. His first exposure to technology as a true educational tool came when his father bought him an Android phone.

That device opened up the world: he discovered programming through small apps, used the internet to access books and treated technology as a gateway to opportunity.

For him, AI feels like a natural continuation of that journey. Just as a phone or a library leveled the playing field for him, he believes AI can give students everywhere—including those in underserved communities—a fairer shot at learning.

“AI can level the playing field,” Mutombo said. “Imagine a student in a third-world country with just a smartphone—instead of spending hours on Google, they could get information in minutes with AI.”

Even professors like Carmichael—who are strong advocates of working independently of AI—see the value in using it as a tool.

“AI is excellent for proofreading and for giving feedback like a writing instructor—identify awkward sentences, smooth transitions—without rewriting for you,” said Carmichael.

The consensus between faculty and students seems to be that AI is an effective tool if used correctly and with integrity.

“Responsible use is when AI helps you think through problems—like walking me step-by-step through a calculus example and explaining why,” said Mutombo.

Mutombo finds that embracing AI will allow one to evolve with society and gain skills which employers find attractive. From his perspective, faculty needs to embrace AI instead of discouraging students from using it.

“Frowning on AI won’t make it go away. The best approach is to empower students to use it effectively and ethically,” said Mutombo.

Carmichael agrees, though he notes that AI usage, when done fraudulently, can impact others negatively. Curved grading can tempt otherwise honest students to cheat so they don’t feel that AI misuse is their competitor. He advocates for integration of such tools but as just that—tools.

“Simply discouraging AI won’t work; we need clear expectations and better tools,” said Carmichael. “We must address cheating and, at the same time, use these tools to make learning richer and more effective.”

As an institutional response, IU Indianapolis has introduced an AI-focused course to help students use it responsibly. At the beginning of the semester, students were invited to accept the GenAI 101 course on their Canvas dashboard. Totaling about three hours, completion of the course would result in four badges: AI Interaction and Prompting, AI Content and Verification, AI for Problem Solving and AI for Communication and Creativity. Together, this would award one with a GenAI 101 Certified microcredential.

Rather than blanket bans, the school is experimenting with education-first approaches. There are even generative AI tools which IU students are given exclusive access to from ChatGPT Edu to Microsoft 365 Copilot Chat.

As technology advances, the question of whether AI will make education richer or become an overreliance which erodes what makes learning valuable will remain. In the meantime, professors want students to take advantage of their time in college and the opportunity to learn.

“College is a special opportunity to become an interesting, well-educated person. If you use AI illicitly, you lose that benefit and stall your intellectual growth,” said Carmichael.

Salsabil F. Qaddoura is the Campus Editor and Financial Officer of The Campus Citizen. She is an undergraduate student on a pre-law track with a minor in business. She is passionate about public service and volunteerism to better our communities and the world.